New research from Medical English Specialist Ros Wright explores how NHS Clinical Educators Workshops provide NHS trusts with the platform needed to support OET test-takers on their educational journey.

New research from Medical English Specialist Ros Wright explores how NHS Clinical Educators Workshops provide NHS trusts with the platform needed to support OET test-takers on their educational journey.

Classroom to Hospital Ward: Supporting OET candidates in the workplace

By Ros Wright, co-author of Cambridge University Press' Good Practice: Communication Skills in English for the Medical Practitioner (2008).

Introduction

With UK hospital trusts reporting 100,000 vacancies (The Health Foundation, 2019), the demand for overseas staff and therefore OET has never been greater. However, preparing candidates for industry-specific tests such as OET can be challenging. This article describes an initiative to enlist nurses and clinical educators within the workplace to provide additional support to candidates as they train for OET.

Workplace relevance

Research points to OET as a ‘good indicator of workplace readiness’ (Vidakovic & Khalifa, 2013), both in terms of language proficiency and acculturation (Macqueen et al, 2013) which explains its popularity amongst employers. Indeed, when mapped against the NMC’s Future Nurse: Standards of Proficiency, one can see a noticeable correlation with the marking criteria for the OET Speaking sub-test (fig 1).

[Fig 1]

| Future Nurse: Standards of Proficiency | OET Speaking Criteria (Clinical Communications) |

|

1.1 Actively listen, recognise and respond to verbal and non-verbal cues 1.2 Use prompts and positive verbal and non-verbal reinforcement 1.3 Use appropriate non-verbal communication including touch, eye contact and personal space 1.4 Make appropriate use of open and closed questioning 1.5 Use caring conversation techniques 1.6 Check understanding and use clarification techniques 1.7 Be aware of own unconscious bias in communication encounters |

· Building the relationship with the patient (listen actively, empathize, reassure the patient, ask for consent) · Understanding and incorporating the patient’s perspective (elicit patient concerns, pick up on cues, relating explanations to elicited ideas) · Gathering information (use open and closed questions, clarify and summarize information) · Providing structure (sequence logically, increase patient recall and adherence) · Giving information (establish what the patient knows, check the patient has understood) |

OET Handbook for NHS Clinical Educators, 2019

The NMC’s emphasis on accuracy, clarity, and legibility is conceptualised in greater detail in the six OET Writing assessment criteria (fig 2).

[Fig 2]

| Future Nurse: Standards of Proficiency | OET Writing Criteria |

|

1.8 Write accurate, clear, legible records and documentation 1.9 Confidently and clearly present and share […] written reports with individuals and groups 1.10 Analyse and clearly record and share digital information and data 1.11 Provide clear [….], digital or written information and instructions when delegating or handing over responsibility for care |

· Purpose (write clearly emphasising the purpose) · Content (include all necessary information, ensure accuracy) · Conciseness & clarity (omit unnecessary information for an effective summary) · Genre & style (use register, tone, abbreviations appropriate to the reader) · Organisation & layout (organise and lay out letter to maximise understanding) · Language (use appropriate grammar, lexis, spelling, punctuation to communicate necessary information) |

OET Handbook for NHS Clinical Educators, 2019

Compared to other proficiency tests, familiarity with the language and tasks presented in OET results in increased candidate buy-in and motivation. Candidates also appreciate OET’s workplace relevance: ‘OET helped me in gaining communication skills with patients and other health professionals. Now I can use some expressions in calming patients, showing empathy to patient which I knew but never used before.’ (Vidakovic & Khalifa, 2013).

Context

In the UK, overseas nurses are either recruited from abroad (e.g. India, Philippines, EU), or locally, i.e. from a pool of healthcare assistants or unregistered nurses already working in the NHS. Hospital trusts may fund OET preparation courses as part of the candidate’s contract. However, some may require these nurses to pass OET within 6 months, after which time they either continue working as unregistered nurses and self-fund their study or return home.

Given the stakes, trusts are eager to provide additional support to their OET candidates. Yet, for the nurses and clinical educators involved, this often proves challenging. Many agree they lack sufficient understanding of the test structure as well as the level of English required to be successful. They feel ill-equipped, not only to determine test-readiness, but also to advise and manage candidate expectations. Disassociating the clinical element of OET from the language aspect also poses problems. As non-linguists, nurses/educators are unsure of their role.

In response, Cambridge Boxhill Language Assessment designed the NHS Clinical Educators Workshop to provide practical knowledge and skills to help those concerned bridge the gap between the English language classroom and the hospital ward. These workshops aim to improve levels of support for OET candidates and so maximize their chances of success.

OET experience

The workshop begins by throwing its clinical educator participants in at the proverbial deep-end as they carry out a typical role-play from OET Speaking. Putting participants in the shoes of the candidates develops an understanding of the test and highlights potential challenges. It also demonstrates OET’s workplace relevance and the subsequent impact on the candidate’s future contribution to both individual patient care and the hospital team as a whole.

Role of Nurses/Nursing Educators

The most important aspect of the workshop is to establish a clear role for the nurses/educators in the candidate’s OET journey.

Key to success in OET Speaking is the demonstration of a patient-centred approach to care assessed both linguistically and via the clinical communications criteria in fig 1 which stem from the concept of patient-centred care. However, depending on their initial training, some candidates may be unfamiliar with this approach. Furthermore, while OET trainers will be adept at developing candidates’ linguistic skills and test-taking strategies, they are often less au fait with healthcare discourse and the effect on patient care. Consequently, nurses/educators provide an invaluable contribution by filling knowledge gaps and giving insight into the healthcare system, work culture and patient expectations. Nurses/educators can also offer additional opportunities for language practice; some candidates are denied sufficient exposure to the target language, either because they work night shifts and/or by the fact English is not spoken at home.

As candidates put their newly acquired skills into practice on the hospital ward, the nurses/educators can model effective verbal and nonverbal communication as well as provide feedback on communicative competency. The added benefit is that such support can be provided in the workplace and in real-time, either immediately following a patient encounter or at the end of a shift. Indeed, this is the environment where nurses/educators can feel most at ease; their task being an extension of their existing mentor role.

Language learning and test-taking

The next part of the workshop ensures participants leave with a basic grasp, both of the language learning process, and the candidate’s perspective: their relationship with English, their motives and challenges, etc. Some candidates speak a variety of English and have completed their studies in the target language, while others have learnt English as a foreign language, but rarely in the context of healthcare. The latter face the usual hurdles of adult ESP learners, notably the mismatch between cognitive and linguistic capabilities; hurdles which are further compounded by the high stakes involved. The former, on the other hand, might struggle with aspects of delivery, such as intonation, or use features which differ from more standard forms of English tested in OET, e.g. overuse of present continuous amongst S. Asian speakers.

Participants are introduced to features of languages spoken by candidates and the impact these might have - positively or negatively - on their performance in English. Examples of this include Spanish candidates who find differentiating between voiced and voiceless consonants challenging or candidates whose mother tongue has only one present tense, e.g. Polish. Both features can affect fluency and accuracy during a patient encounter. Filipino nurses tend to have a good rapport with patients, in part due to similar intonation patterns between Tagalog and English; a feature that is essential when conveying empathy and sensitivity effectively to a native speaker. However, referring to the comfort room rather than the toilet, means influence from US English can cause unnecessary confusion.

Finally, the group considers reasons for poor test performance, including the correlation between test-taking anxiety and female test-takers. From a wider perspective, candidates are also grappling with a multitude of personal factors, from feelings of homesickness to fitting study around work and family commitments, all of which can have a bearing on test performance.

Test readiness

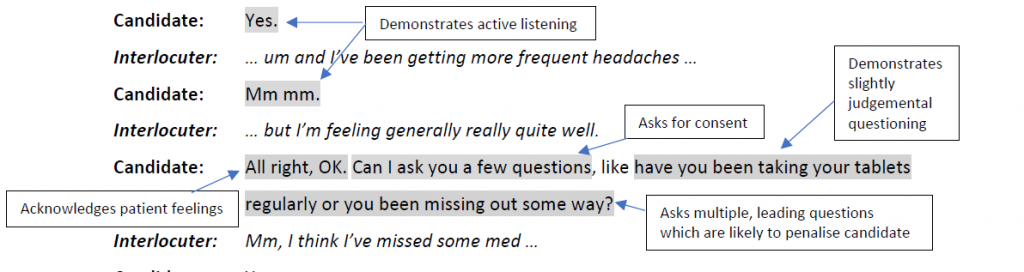

Next, participants use the communications criteria (fig 1) to grade two sample role plays. They are surprised to learn how a seemingly fluent speaker of English might only attain an average clinical communications score (fig 3) resulting in a borderline grade in OET Speaking.

[Fig 3]

OET Handbook for NHS Clinical Educators, 2019

Correction Techniques & Activities

In the final part of the workshop, nurses/educators are introduced to techniques and activities to help support their candidates. Participants practice gestures, echoing and reformulating for on-the-spot correction and, where delayed correction is more appropriate, are guided on how to deliver sensitive but effective feedback. Auto-correction is highlighted as the goal for candidates (within reason) and self-reflection is encouraged to further foster learner autonomy.

A handbook contains a series of 5-minute activities for use with candidates. These include ideas for developing fluency and devising role-play scenarios, e.g. images of clinical procedures and functional language typically assessed during OET Speaking (explore the reason for the patient visit, reassure the parent, etc.). Participants are reminded of the benefits of recording role-plays to review communication skills and provide meaningful correction and feedback.

Suggestions for additional support and promoting collaborative study include a dedicated WhatsApp group providing information about OET events (webinars, Masterclasses, etc.), a study buddy scheme and a meet-up group to share test-taking strategies and study tips. While inviting a colleague - a successful OET candidate - as guest speaker will undoubtedly prove highly motivational.

Conclusion

Response has been largely positive. Arguably, the workshop is as much about instilling confidence in the nurses/educators and reassuring them of their role, which is key to providing effective support to OET candidates, as building pedagogical skills. Familiarising participants with the test papers prior to the workshop would be beneficial. Similarly, providing tools to help transmit the message that OET is a test of English and not clinical knowledge. Ultimately the role of nurses/educators is not to replace the OET trainer but rather to complement them, to provide the candidate with invaluable exposure to and feedback on real-world communication and promote cultural adaption. This leads not only to increased success at OET but most importantly to guaranteed patient safety and well-being once the candidate is in the workplace.

Bio

Ros Wright has 20 years’ experience in English for medical purposes and devised the NHS Clinical Educators Workshop for Cambridge Boxhill Language Assessment. She is co-author of several coursebooks in this field, her latest is OET Speaking & Writing Skills Builder (Express Publishing, 2020). A former President of TESOL France and General Secretary of EALTHY, Ros is currently a Trustee of IATEFL.

References

Buchanan, J. et al (2019) A Critical Moment: NHS Staffing Trends, Retention and Attrition, The Health Foundation

Macqueen, Pill, Elder, Knoch (2013). Investigating the test impact of the OET: A qualitative study of stakeholder perceptions of test relevance and efficacy, Language Testing Research Centre, The University of Melbourne

Vidakovic & Khalifa, (2013). Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Occupational English Test (OET): An exploratory study, Cambridge English : Research Notes, Issue 54